Two primary options often come to mind when creating a project to showcase your skills, generate buzz, or attract investors: short films and proof of concepts. Both have their strengths and weaknesses, and deciding which is right for your project largely depends on your goals, resources, and the story you want to tell. Let’s break down the differences between the two when to use each, their pros and cons, and examples of successful films that started as shorts or proof of concepts. Finally, I’ll share my take on when each format works best.

What Is a Short Film?

A short film is a complete, standalone story that typically runs under 40 minutes. It has a full narrative structure with a beginning, middle, and end, making it a fully realized creative piece. Short films are often used as calling cards to demonstrate a filmmaker’s talent in storytelling, directing, and technical skills. They can be powerful in conveying a message or showcasing a filmmaker’s unique vision.

Key Uses of a Short Film:

- Film Festivals: Short films are often submitted to festivals for exposure, awards, and networking opportunities.

- Portfolio Piece: It’s a great way to show potential collaborators or investors what you can do with a full story.

- Monetization: After a festival run, short films can be sold to streaming platforms, used as part of a digital distribution strategy, or even monetized via platforms like Vimeo On Demand or YouTube’s partner program.

Examples of Short Films That Became Features:

- “Whiplash” by Damien Chazelle started as a short film that premiered at Sundance. It was so well-received that it became a full-length feature, winning multiple Oscars.

- “Saw” by James Wan initially began as a short horror film used to pitch the idea to studios. The feature went on to spawn a massive horror franchise.

- “Napoleon Dynamite” originated from a short called Peluca. The success of the short helped secure funding for the beloved indie comedy.

What Is a Proof of Concept?

A proof of concept (PoC) is not a full story but rather a focused, visual pitch meant to demonstrate a key aspect of a larger project. The goal of a proof of concept is to convey the potential of a full-length feature, series, or documentary to investors, studios, or networks. These projects are shorter than short films and hone in on specific elements like tone, style, or a key scene that captures the essence of the larger work.

Key Uses of a Proof of Concept:

- Pitching a Larger Project: A proof of concept can serve as a pitch tool for a feature film, TV series, or documentary. It shows how your project will look, feel, and function without the need to create a full version.

- Attracting Investors: Because proof of concepts are shorter and more focused, they’re ideal for attracting funding or investment, especially for high-budget projects like series or large-scale films.

- Testing Ideas: A proof of concept can help you gauge audience or industry reaction to your idea before fully committing to production.

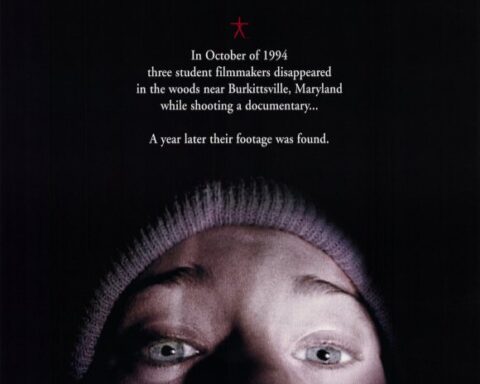

Examples of Proof of Concepts That Became Features:

- “District 9” by Neill Blomkamp originated from a short proof of concept called Alive in Joburg. The proof of concept impressed producer Peter Jackson and secured the funding for the feature-length film.

- “Mama” by Andy Muschietti began as a short horror film that caught the attention of Guillermo del Toro, who helped develop it into a feature-length movie.

- “Lights Out” by David F. Sandberg started as a short, spine-chilling proof of concept that led to a successful feature film.

Pros and Cons of Short Films vs. Proof of Concept

Short Film Pros:

- Complete Storytelling: You can tell a full narrative, showcasing your ability to create characters, build tension, and resolve plot points.

- Festival Opportunities: Short films are widely accepted in film festivals and can lead to significant exposure, awards, and networking.

- Monetization: Post-festival monetization is possible through streaming platforms or pay-per-view sites.

Short Film Cons:

- Budget & Time-Intensive: A short film requires more resources and time to complete, as you’re crafting a complete story with a full cast, production, and post-production.

- Limited Audience for Investors: While great for festivals, short films may not always hook investors looking for feature-length projects.

Proof of Concept Pros:

- Clear Pitch for Larger Projects: PoCs are ideal for pitching to studios and investors, allowing them to visualize the potential of a larger film or series.

- Budget-Friendly: Since PoCs focus on specific scenes or concepts, they are often cheaper to produce than a full short film.

- Targeted Impact: You can focus on the key aspects that will sell your project, like tone, visuals, or special effects, without committing to a full story.

Proof of Concept Cons:

- Incomplete Narrative: PoCs usually don’t have a full story arc, which can make them less appealing to general audiences or festivals.

- Not Suitable for All Projects: If your goal is to tell a standalone story, a proof of concept won’t serve your needs as well as a short film.

When Should You Choose a Short Film?

If you’re aiming to create a complete project that qualifies for grants, film festivals, and potential monetization after its festival run, a short film is the way to go. Short films are particularly useful if you’re an emerging filmmaker looking to showcase your storytelling abilities. They allow you to enter the festival circuit and gain recognition, potentially leading to opportunities for larger projects.

For example, Whiplash started as a short film, which helped director Damien Chazelle secure financing for the feature-length version. Similarly, Napoleon Dynamite proved that a quirky, self-contained story could capture an audience’s imagination and transition into a feature.

When Should You Choose a Proof of Concept?

Proof of concept are perfect for projects that have a larger scope, like TV series, documentaries, or high-concept feature films. In these cases, a full short film might not convey the depth or scale of the project. Instead, a PoC allows you to demonstrate key elements, like visuals, tone, or world-building, without the need to tell the whole story.

For instance, District 9 began as a proof of concept that demonstrated Neill Blomkamp’s ability to blend science fiction with social commentary. The short was powerful enough to attract the attention of Peter Jackson, who then produced the full-length feature.

I personally favor using PoCs for projects that require a lot of information, such as documentaries, TV series, or reality shows. These formats need a clear pitch of style and tone, and a PoC can effectively showcase the potential of these types of projects. However, I don’t recommend using PoCs for every type of project—especially if your goal is to submit to festivals or tell a complete story.

Budget Considerations for Both Formats

Short Film Budget:

- Average Range: $5,000 – $50,000+

- Focus: Invest in creating a polished, complete narrative with strong production value. You’ll need to budget for cast, crew, locations, equipment, and post-production. It’s essential to plan for festival submissions and potential marketing if you aim to distribute your short after the festival run.

Proof of Concept Budget:

- Average Range: $1,000 – $20,000

- Focus: Prioritize visuals, tone, and the elements that will sell your larger project. Since you’re not telling a full story, your budget can be more focused on high-quality cinematography, impactful scenes, and any special effects needed to bring your concept to life.

Regardless of whether you choose a short film or a proof of concept, both formats are valuable tools in attracting investors, studios, or distributors. If you’re planning to eventually make a feature film or multi-season series, either format can serve as a stepping stone to securing the necessary funding.

My Take on Short Films vs. Proof of Concepts

I root for short films because they give you a complete project that qualifies for grants, film festivals, and monetization opportunities. There’s something powerful about presenting a finished product that audiences and critics can enjoy in its entirety.

However, I only recommend proof of concepts for documentaries, TV series, and reality shows. These types of projects often have more moving parts and benefit from a focused visual pitch rather than a full narrative. A well-executed proof of concept can give investors a clear sense of what the final project will look like, without needing the entire story laid out.

Both formats can set you up to find investors for larger projects, whether that’s a feature film or a TV series with multiple seasons. For instance, a project like Suicide Games is perfect for a proof of concept, where the concept’s tone and visuals are key selling points. On the other hand, Smile from A24 could have done well as a short film before expanding into a feature, showcasing its full horror narrative.

Conclusion:

Whether you decide to create a short film or a proof of concept depends on your overall goal and budget. If you’re looking for festival exposure and a complete project, go for a short film. If you need to pitch a larger idea or project, especially one that requires investor buy-in, a proof of concept may be your best bet.

Make sure to check out my blog for a more detailed comparison between short films and proofs of concept, and feel free to ask me any questions!